rethinking treg

the two controversies that matter

In the theoretical and opinion papers published in Immunology & Cell Biology and Clinical & Experimental Immunology by the Ono group, traditional views on thymus-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) are challenged (Ono & Tanaka, 2016; Bending & Ono, 2018).

Two Core Controversies

The Non-Reproducible Evidence for Thymus-Derived Treg

For years, the immunology community has recognized Tregs as a distinct, genetically programmed T-cell lineage crucial for immunosuppression. However, given the plasticity and dynamic regulation of Foxp3, the ‘lineage’ transcription factor for Treg, it is more straightforward to understand the temporal dynamics of Foxp3 expression over time, rather than assuming the stability of a unique T cell ‘lineage’.

Why do we still consider that Treg are distinct and unique?

For those who are TCR-seq ‘fans’ — the answer isn’t TCR. Since all T cells, including Tregs, exhibit uniqueness through their T-cell receptors (TCRs), it is misleading to single out Tregs as uniquely distinct based on TCRs alone. All T cell subsets exhibit this form of uniqueness; thus, apart from their ‘self-reactivity’, Tregs are not uniquely unique.

Furthermore, ‘self-reactivity’ isn’t exclusive to Tregs. I will delve deeper into this topic in an upcoming article.

The answer is here – the belief is primarily based on evidence that CD25+ Tregs migrate to the neonatal spleen later than their counterparts and that early thymectomy in mice leads to Treg depletion and autoimmune diseases (Asano et al, 1996).

Many esteemed immunologists appreciated this finding and accordingly established the current field of Treg research. However, Ono and Tanaka reviewed the literature, identifying contradicting evidence and noting that such foundational evidence has never been effectively reproduced, with key studies demonstrating the presence of Tregs in neonates.

Thus, simply speaking, there is no such thing as “a distinct, genetically programmed T-cell lineage crucial for immunosuppression.” There is only a status of T-cells in which Foxp3 is expressed and operating.

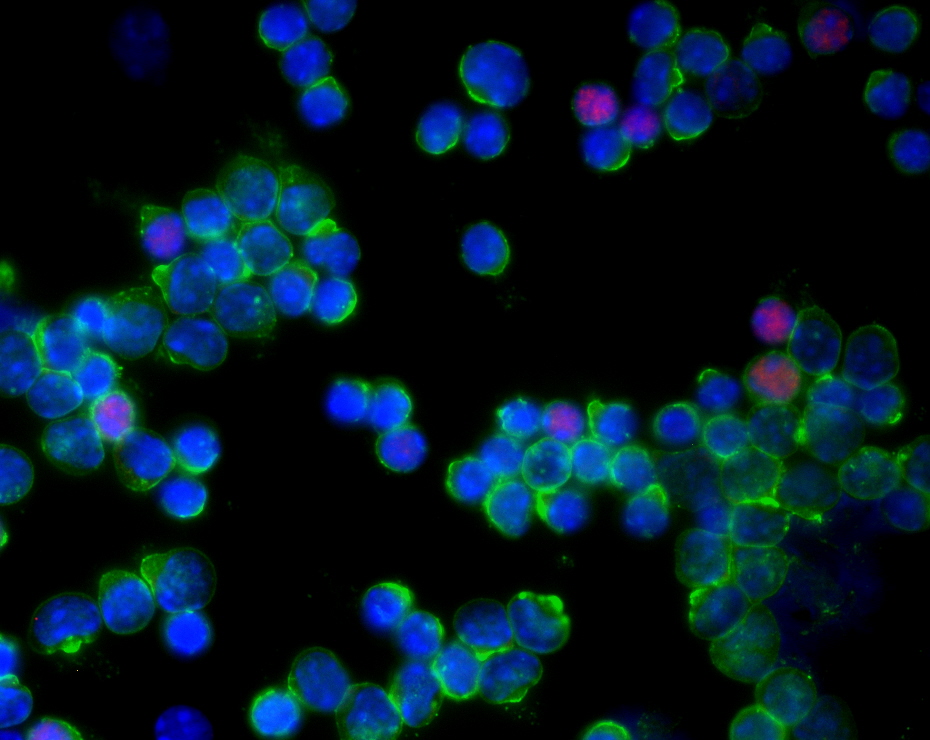

The article by Ono and Tanaka proposes a theoretical model: viewing Tregs not as a separate lineage but as an integral feedback mechanism for T-cell activation within the T-cell system. This conceptual shift was established as the foundation for Ono to further advance our understanding of T-cell regulation by investigating Foxp3 dynamics using the Foxp3-Tocky model.

Read the full paper here (Ono & Tanaka, 2016).

Lessons from the TGN1412 Clinical Trial —the World’s First Attempt at Treg Therapy

In a recent study from our lab, the dynamics of Foxp3 transcription were examined as key to understanding Treg-mediated immune regulation (Bending et al., 2018). This study highlights the importance of viewing Tregs not just as a distinct lineage but as part of a dynamically regulated immune system.

The catastrophic clinical trial of TGN1412 in 2006, which resulted in cytokine storm and multiorgan dysfunction in volunteers, serves as a stark reminder of what can go wrong when this dynamic is not fully understood. TGN1412, initially developed to suppress autoimmune reactions by targeting Tregs specifically, inadvertently activated a broad range of T cell responses following CD28 stimulation.

The investigation into this incident concluded that a major factor was the ‘unexpected difference between species’ concerning the use of CD28. However, this raises a critical question: should it have been anticipated that CD28 could stimulate a wide array of T cells?

This case highlights the critical need for a deeper understanding of Treg plasticity and the dynamic nature of T cell differentiation and activation.

Read the full paper on TGN1412 and Treg dynamics here (Bending & Ono, 2018).

Implications for Future Research

The core message of these publications highlights the importance of understanding the dynamic molecular processes within T cells. Scientifically, viewing Treg as a status of activated T cells and analysing Foxp3 to investigate their function could lead to more precise interventions in autoimmune diseases, enhanced immunotherapy approaches, and a deeper understanding of T-cell dynamics.

Beyond the scientific challenges, a fundamental issue remains: the need for greater research integrity and transparency. In a field often influenced by closed circles of a limited number of ‘established scientists’, who financially benefit from ‘advances’ in immunotherapy, we must ask ourselves: are we truly prepared to embrace this necessary openness?

The journey is far from over. I am eager to continue this research and look forward to sharing further insights.

References

2018

- From stability to dynamics: understanding molecular mechanisms of regulatory T cells through Foxp3 transcriptional dynamicsClinical and Experimental Immunology, Sep 2018

- A temporally dynamic Foxp3 autoregulatory transcriptional circuit controls the effector Treg programmeThe EMBO journal, Sep 2018The second Tocky paper from the Ono lab uncovers the temporally dynamic regulation of Foxp3 transcription, offering new insights into T cell regulation.

2016

- Controversies concerning thymus‐derived regulatory T cells: fundamental issues and a new perspectiveImmunology and cell biology, Sep 2016A landmark opinion piece challenging the reproducibility of a foundational Treg experiment, while introducing a groundbreaking dynamic view on Foxp3-mediated T cell regulation.